Welcome to the Ocean Health Index (OHI)! OHI is the first assessment framework that combines and compares all dimensions of the ocean - ecological, social, economic, and physical - to measure how sustainably people are using ocean and coastal resources.

You are currently at the first of four phases of conducting an OHI assessment - the Learn Phase. Here you will get an overview of the OHI framework, its workflow, what to expect from an OHI assessment, and how the scores are calculated, in order to prepare yourself for the next planning phase of an assessment. You will also be introduced to the philosophy behind each OHI goal.

For a more in-depth look at OHI and its process, check out our other web materials, including Presentations, and Publications. If you want to know more about how to define and measure each goal, visit the Goals page.

Let’s get started!

1 Introduction

The OHI framework assesses a suite of key social, economic, and ecological benefits a healthy oceans provides, called “goals”. By analyzing these goals together and scoring them from 0-100, OHI assessments result in a comprehensive picture of the state of the ecosystem and can be communicated to a wide range of audiences.

In the OHI framework a healthy ocean is one that sustainably delivers a range of benefits to people now and in the future. The Ocean Health Index is not an index of ecosystem services. In creating an inventory of all elements that are considered part of a healthy ocean under a wider definition, various categories began to evolve. The ten goals (and eight sub-goals) that are commonly included in an Index broadly capture the universal ocean benefits:

Food Provision from sustainably harvested or cultured fish stocks

Artisanal Fishing Opportunities for local communities to engage in sustainable practices

Natural Products that are sustainably extracted from the ocean

Carbon Storage in coastal habitats

Coastal Protection from inundation and erosion

Sense of Place from culturally valued iconic species, habitats, and landscapes

Livelihoods and Economies from coastal and ocean-dependent communities

Tourism and Recreation opportunities

Clean Waters and beaches for aesthetic and health values

Biodiversity of species and habitats

This framework was first applied to the global scale in 2012, and since then, numerous independent groups have adopted the framework to assess ocean health in their own countries or regions. Although conducted at different spatial and temporal scales, all OHI assessments follow the same workflow.

1.1 Four Phases of OHI+

There are four phases of OHI+ assessment: Learn, Plan, Conduct, and Inform. You are currently in the Learn Phase, where you will understand OHI framework and philosophy, and determine the needs and purposes of your OHI+ assessment.

1.2 OHI Workflow

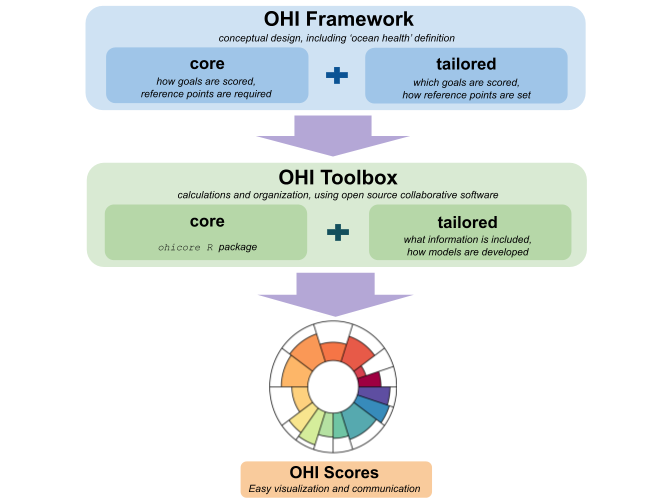

You will first build a conceptual framework and determine which goals to access and how, which is then translated into the toolbox to calculate the scores. Both the conceptual framework and technical toolbox consist of two major parts: core and tailored. The “core” maintains the integrity of Ocean Health and determines how Index scores are calculated, while the “tailored” allows flexibility and accommodates different scales, data availabilities, and cultural priorities.

OHI+ teams are responsible for modifying the “tailored” part of the framework and toolbox, thereby truly ensuring local adaptation. Besides incorporating local data, a large part of tailoring involves choosing and modifying goal models. While the 10 goals identified in the Index represent broadly-held public benefits globally, they might not apply to your local territories. We provide detailed instructions on how to choose and change your own goals in the Conduct phase.

1.3 Outcomes of an OHI+ assessment

Your completed assessment will produce OHI scores for each goal in every region of your study area, and scores within the assessment can be compared with one another. Goal scores range between 0 and 100, and are visualized in a Flower Plot for easy communication with a wide audience - each pedal represents one goal or subgoal, and the size of the pedal corresponds with its score. (Note: the colors of the pedals match those of goal icons and do not correlate with scores.)

However, these scores will not be quantitatively comparable to those of other OHI assessments because they differ in the underlying inputs, goal models, and reference points.

![]()

1.4 What support we provide

Our team of scientists and managers is prepared to provide guidance for regional assessments, from initial meetings to the technical calculations to disseminating results. We have created a suite of guides and manuals that provide in-depth information for the Ocean Health Index+ assessment process in addition to recommendations on how to best approach the task, including:

A Guide to Planning OHI+ Assessments and Informing Decision-Making

The Ocean Health Index Toolbox Manual

In addition, you will have access to the OHI+ online community via our Forum

2 Global Assessments and Your OHI+ Assessment

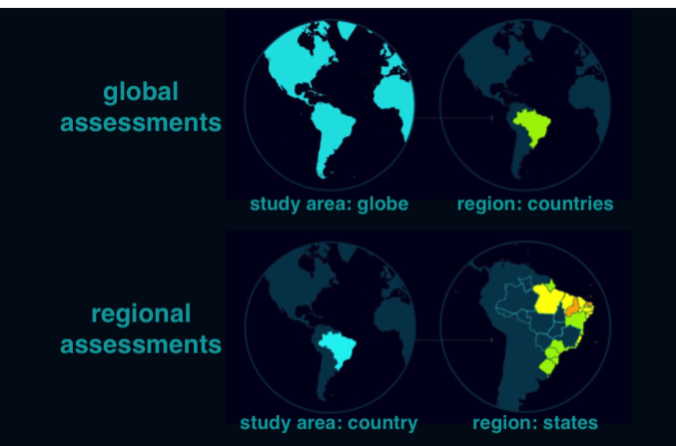

By conducting a OHI+ study, you will be developing an Independent Ocean Health Index at a spatial scale of your choice. Most OHI+ assessments take place at subnational scales (states, provinces, municipalities) and then are aggregated at a national scale. However, you can implement the OHI methodology at any scale from global, to transboundary regions, to subnational areas.

OHI+ assessments are conducted by independent groups such as yours that use the Index framework to measure ocean health in their own regions, countries, states, and communities. Your OHI+ assessment is different from the Global Assessments because they are meant to fit your local context. The purpose of conducting these independent assessments is that they be used by managers in your area to incorporate information and priorities at the spatial scale where policy and management decisions are made. The overarching OHI framework should guide your efforts, but you should determine the data, models, and other inputs that go into your assessment in order to make it more relevant to management in the local context.

The Index framework remains consistent at different scales. Whether at the global level, as in the Global Assessments, or at your more local level, the goal scores are calculated at the scale of the reporting unit, or region, and scores are then combined using a weighted average to produce the score for the overall area assessed, called the study area.

In the Global Assessments the study area is the world and the regions assessed are two hundred twenty coastal countries or territories, Antartica, and the fifteen regions of the High Seas in an even more recent study. At the global scale, the regions are defined by internationally recognized Exclusive Economic Zones. Global assessments are conducted by a multidisciplinary team of scientists led by the U.S. National Center for Ecological Assessment and Synthesis (NCEAS), Conservation International, and the Seas Around Us Project. These studies are published annually and use models developed using the best existing data available at the global scale to capture each goal philosophy (which will be described in later sections of this phase).

2.1 Comparing Scales of Assessment

It is important to note that the scores from your OHI+ assessment cannot be compared directly to the scores from Global Assessments or other independent assessments. Since your goal choices, goal models, and input data and parameters will differ from those employed globally, your methods will be unique to your area, meaning the scores cannot be quantitatively compared. However, you can compare the scores for the same assessment area through time and make truly quantitative comparisons. Understanding this should allow you to be creative as you develop your plans going into your assessment. Nevertheless, it is possible to make qualitative comparisons. For example, although methods may differ between two independent assessments, it is possible to say that country X with a score of 80 is closer to its management targets than country Y with a score of 65.

3 Determine the Need and Purpose of Your OHI+ Assessment

Remember that producing the Index is not the end in itself – the aim is to achieve improved ocean health. Defining the end-goals of the study will largely determine how goal models, data gathering, and reference points are developed to maximize the utility of the findings to inform decision-making, and is very important in ensuring a smooth and successful project with OHI+.

OHI+ is applied research, aiming at solving practical problems related to ocean and coastal resource management. One of your first tasks when developing an OHI+ assessment should be to define the purpose of the study and think about how it can complement other or planned efforts of environmental management. Assessments should be conducted with clear research questions in mind–how will the assessment help achieve improved ocean health? How will the assessment help address specific problems and needs in the study area?

Perhaps you want to better understand ocean and coastal health in your region, or you are actively engaging in ecosystem-based management, or you are facilitating a multi-stakeholder collaborative planning and target setting process. Regardless of your reasons, you can use this site so at the end of your assessment, you will have established a baseline estimation of the status of ocean health in your study area, and use that information to determine how well you are meeting, exceeding, goal targets in certain indicators.

Assessments provide an opportunity to put in place a multi-stakeholder collaborative process. In our experiences engaging with various countries around the world, the most effective assessments are those where the process of conducting the assessment was just as valuable (if not more) than the final results. This is because the assessment process serves as a forum to engage stakeholders from multiple backgrounds (scientific, civil society, government, private sector, NGOs, etc.) to discuss local preferences and priorities, understand the interactions between various activities, and collaboratively establish management targets.

On the technical side, the process is also valuable because it allows the users to synthesize collections of data, scientific findings, and management efforts. An important theme throughout this process it to find metrics that are meaningful your area.

3.1 Choose the study area and set boundaries

Carefully choosing the study area and the regions to evaluate in the assessment certainly plays an important role in defining the purpose of the study. When defining the spatial scales of the assessment, consider the following: Will your regions match the scales of decision-making, will they match biogeography, or will they try to fit both? Will this require new data, or will it require involvement and the collaboration of neighboring countries?

See the Baltic Health Index for an example of regional collaboration. Once you have a sense of your regions of interest, you should also consider whether other efforts are already underway to manage those areas and whether researchers are active in the area. This could lead to new opportunities for collaboration, and for chances support new data-collection efforts. You should aim to align your OHI+ assessment with existing management objectives and initiatives to reduce redundancy and maximize the utility of existing resources. As you begin planning the assessment, do consider the policy and scientific strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) of conducting a study your area.

In addition, there are some considerations in this step that will prove helpful later in the assessment:

-

Do some preliminary scoping - is this feasible in the proposed study area?

-

Begin thinking of the objectives, scope, scale, and key actors to involve in the process; this will make Phase 2 much easier to tackle

-

Understand which goals and ocean benefits are important in the proposed study area, and what threats or possible changes might be affecting the sustainable delivery of those benefits

4 How OHI Scores Are Calculated

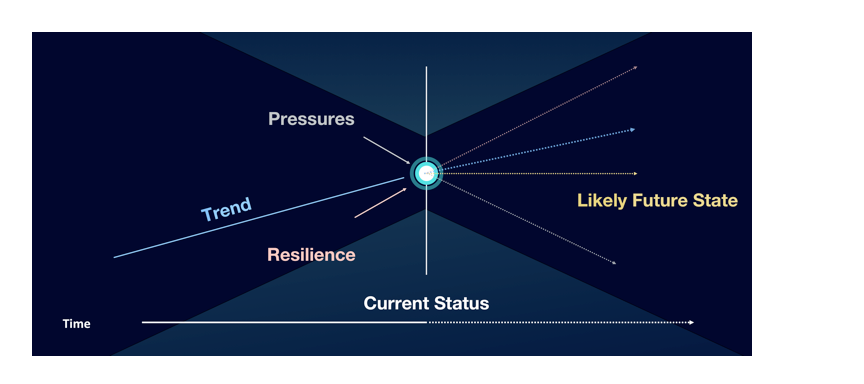

Total Index is the weighted average of individual goal scores. Each goal measures the delivery of specific benefits with respect to a sustainable target. A goal is given a score of 100 if its maximum sustainable benefits are gained in ways that do not compromise the ocean’s ability to deliver those benefits in the future. Lower scores indicate that more benefits could be gained or that current methods are harming the delivery of future benefits. Each goal score has two major components: current status and likely future state.

The current status is determined by comparing the most recent measure of the goal against a goal-specific sustainable Reference Point. It represents half of a goal’s total score.

The other half is the likely future state, which is current status modified by the trend, pressures, and resilience:

-

Trend: the average rate of change in status during the most recent years. As such, the trend calculation is not trying to predict (or model) the future, but only indicates the likely condition (sustainability) based on a linear relationship.

-

Pressures: social and ecological elements that negatively affect the status of a goal

-

Resilience: social and ecological elements (or actions) that can and reduce pressures, and maintain or raise future benefits (e.g. treaties, laws, enforcement, habitat protection)

In the figure, likely future state (in yellow) is the result of the trend, minus the negative effect of pressures (grey), plus the positive effect of resilience (salmon pink)

Pressures and resilience are important for scores, although they have a smaller contribution to the overall scores because we can only approximate their effects. Individual pressures are ranked (weighted) according to their importance to different goals based on scientific literature and expert opinion. From a management intervention perspective, resilience actions are the best way to improve a score, because they can reduce pressures, protect ocean habitats and species, improve status, and optimize benefits to people.

4.1 How are the goals weighted?

In the Global Assessment the goals are weighted equally to maintain objectivity since different countries have varying subjective preferences and priorities for weighing the goals. However, in your OHI+ assessment the weighting can be changed depending on the local context. Stakeholders may have differing priorities, but when presented with the portfolio of goals used in the Ocean Health Index, these differences can become less pronounced, as was found in a study by Halpern et al. (2013) in Marine Policy. This would require good data, of course, such as the information collected through a representatively sample survey. The process of weighing the goals is not a priority as you begin your assessment, however, it is an important feature that can help you understand how different stakeholders perceive the relative importance of various ocean attributes, which can ultimately help you identify priorities and allocate resources in a more effective way.

4.2 Understanding Reference points

To assess how well a goal is being delivered, it is necessary to identify the target to which it will be compared. This target is called the reference point. In an Ocean Health Index framework, setting the reference point enables the numeric values relevant for each goal to be scaled between 0-100 (where 100 means that the current status is equal to the target reference point, and 0 means that it is as far from the target reference point as is possible). Sharing a common range for scores makes all goal scores comparable. There are different types of reference points:

-

Functional relationships: a target determined by a scientifically-informed input-output relationship (an equation called a production function) (most recommended)

-

Temporal comparisons: a target value at some time in the past

-

Spatial comparisons: a comparison with some other location (such as the best performing region)

-

Established targets: a target established by a treaty, law, or other agreement (such as the Convention on Biological Diversity)

It can be advantageous to translate a management target to a maximization or minimization problem with an objective function so that it is clear exactly how an indicator should be developed to track progress. Indeed, these choices significantly influence the evaluation of a goal’s status. For instance, a sustainable seafood management goal could be measured in terms of yields if the goal is focused on maximizing food provision or in number of jobs if the goal is focused on maximizing social and economic welfare. These two goal framings would lead to the development of different targets in terms of both yields and level of employment. Where necessary, our conceptual framework encourages the reframing of management goals to ensure that the corresponding indicators, and the units in which they are reported, accurately portray the intent of the goal as it is stated.

It is important to understand that setting a reference point is a conscious and subjective choice. This choice can be informed by the literature and by expert advice, and can be discussed in terms of costs and benefits. However, ultimately there is no optimum and certainly not only one solution, and this can be very uncomfortable. This makes setting a reference point difficult, but even more important to define explicitly.

We also recommend that there is a consultative and multi-stakeholder participatory process for discussing and establishing reference points. The process for establishing reference points can be rather sensitive since they establish the optimal levels of goal benefits and determine a score of 100. Setting reference points should incorporate SMART principles for target setting: Specific (to the management objective), Measurable, Ambitious, Realistic, and Time-bound (Perrings et al. 2010, 2011). For more information on identifying meaningful reference points and quantifying the current ecosystem state relative to them, refer to Samhouri et al. 2012 Sea sick? Setting targets to assess ocean health and ecosystem services

4.3 Understanding Pressures

A pressure is any kind of stressor on the social or ecological system that is harmful for ocean health, that is, those that have a negative impact on the status of the goal. Pressures represent 8.5% of the total goal score.

Pressures can change how goals interact with each other. For example, raising fish in the Mariculture sub-goal can cause genetic escapes, which are a pressure on the Wild-Caught Fisheries and Species sub-goals. The genetic escapes do not affect mariculture itself, however, and have no effect on that particular sub-goal score while they do have a negative effect on the other sub-goal scores. Understanding the interactions between the goals and in response to specific management actions is one of the ways in which the Index can help inform decision-making.

Pressures are calculated as the sum of the ecological and social pressures that negatively affect goal scores. The Index framework calculates pressures by first grouping them into five ecological categories (pollution, habitat destruction, fishing pressure, species pollution, and climate change) and one social category (governance effectiveness). The reason to pool indicators into categories is to minimize sampling bias, so that no one kind disproportionately influences the score (e.g. if one type of data is disproportionately abundant relative to another it does not imply that the abundant data is more important). They are weighted equally in the global assessment, but in your local assessment they can be changed if there is enough information on how to do so.

4.4 Understanding Resilience

A resilience is any kind of measure on the social or ecological system that is beneficial for ocean health, that is, those that have a positive impact on the status of the goal. Resilience measures represent 8.5% of the total goal score.

Ultimately, it is resilience that will help shape the future of ocean health.

A resilience measure can be a law, policy, management action, or a given performance evaluation that speaks to the effectiveness of actions to improve ocean health. Resilience actions are the best way to improve a score for a study area, because they can reduce pressures, protect ocean habitats and species, improve status over time, and optimize benefits to people. There are different categories of resilience, from institutional, to social, to ecological.

As nation states arose, laws and regulations have steadily evolved to meet their needs. The UN’s main goal was to prevent another world war, but over time it has become the nucleus for international and planetary resilience through programs in peace and security, development, human rights, humanitarian affairs and international law. The UN also organizes treaties such as the Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and programs such as the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals that aim to end poverty and hunger, build healthy lives and well-being, achieve gender equality and empower women and girls; ensure access to sustainable sources of water, sanitation, energy; reduce inequality; combat climate change; create safe and resilient cities and settlements; and use ocean and land sustainably. Though such engagements are entirely voluntary, most countries participate, and the Ocean Health Index considers such participation in calculating resilience scores.

Physical manifestations of resilience also appeared, such as public works projects for worship, defense, transportation, water, sanitation and many others.

4.4.1 Ideal Approach

Ideally, assessments of social resilience would include study area and as well as region specific rules and other relevant institutional mechanisms that are meant to safeguard ocean health. The global focus has been on international treaties and indices, so your region should have more localized information. There would also be information as to their effectiveness and enforcement. Information on social norms and community (and other local-scale) institutions (such as tenure or use rights) that influence resource use and management would be useful too.

For each goal the Index measures several aspects of resilience. Ecological integrity is evaluated as the relative condition of assessed species in a given location and goal-specific regulations including laws and other institutional measures that address ecological pressures. Social integrity is measured as well and describes the internal processes of a community that affect its resilience. Resilience is then calculated as the sum of the ecological factors and social initiatives (policies, laws, indicators of good governance, etc.) that can positively affect goal scores by reducing or eliminating pressures. This is because resilience in the Index framework acts to reduce pressures in each region. Therefore, resilience measures must not only be directly or indirectly relevant to ocean health, but must be in response to a pressure layer affecting a goal.

Although resilience really should be judged by the effectiveness of its outcome, this is not possible at the global level. Therefore, nations are given advanced credit for signing treaties, e.g., for conserving biodiversity or eliminating trade in endangered species, and for measures of social integrity. The assumption is that results from those beneficial actions and conditions will become visible in following years as increased scores for goal status and trend.

4.5 Interactions: Pressures and Resilience

Pressures and resilience layers interact with an indicator to increase or decrease its likely future state. From a management perspective, there are only two ways of increasing the Likely Future State: increase resilience measures and/or decrease pressures. Overtime, the effects of these management actions will change the current state of the goal and the trend, resulting in higher scores. This would be most visible through multiple years of engagement with an OHI assessment.

Ecological and social resilience are assessed separately and then combined to determine the goal score. Although this is usually done through a simple average (with equal weighting for social and ecological resilience measures), it is possible to change their relative weights if expert opinion recommended otherwise. All resilience measure are associated with a pressures layer regardless of the weighting, such that any ecological or social pressure has a countervailing resilience measure. Mathematically, this is represented as r-p, where r=resilience and p=pressures. The Index framework uses this relationship, and the underlying data, to ultimately convey which has a greater incidence over the goal status, the pressures or the resilience.

Pressures and resilience are ultimately important for scores, but they have a smaller contribution (8.5.% each, 17% total) to the overall scores because we can only approximate their effects. Individual pressures are ranked for their importance to different goals based on published studies and expert opinion. Resilience actions are the best way to improve a score, because they can reduce pressures, protect ocean habitats and species, improve status, and optimize benefits to people. In Phase 4, we discuss some strategies for turning your findings into effective resilience strategies.

Pressures and resilience are usually summarized across ecological and social categories in order to reveal the influence of any one factor that might be present. In this way, for example, pressures from pollution, habitat destruction, fishing pressure, species pollution, and climate change will have a cumulative impact on the scores.

4.6 Understanding Trend

The trend is calculated as the slope of the change in status based on recent data. As such, the trend calculation does not model the future status, but only indicates the likely condition assuming a linear relationship. The trend represents a third (33%) of the total goal score.

The trend is, in most cases, calculated using the status score of the last five years. The exact number of most recent years can change depending on the data sources and availability, but the general idea is that the trend conveys the recent history of the indicator. It does this because the trend is then used to calculate the likely near-term future state and can show a reaction to policy interventions.

4.7 Understanding Present Status

The present status component of each goal is captured through a mathematical model (a formula) that captures the philosophy of the goal in a way that produces findings that are most useful to inform decision-making at the scale of your assessment. This dimension represents half (50%) of the total goal score.

The current status of each goal is determined by comparing the most recent measure of the goal with a goal-specific sustainable reference point. For each goal, as well as for many individual data layers, values are rescaled to reference points, or targets, which serve as benchmarks based on SMART principles: Specific (to the management goal), Measurable, Ambition, Realistic, and Time-bound (Samhouri et al. 2012; Perrings et al. 2010; 2011).

5 Philosophy of OHI Goals

In this section we introduce the philosophy for the status of each goal. Here, we introduce conceptually what each goal is intended to capture and what it does not. We provide a more in-depth description of each goal including an Ideal Approach and Practical Guidance on our goals page to help you develop context-specific goal models in the Conduct Phase.

5.1 Food Provision

The aim of Food Provision is to optimize the sustainable level of seafood harvest in your region’s waters.

The aim of this goal is to maximize the sustainable harvest of seafood in regional waters from Wild-Caught Fisheries and Mariculture, or ocean-farmed seafood. Regions are rewarded for maximizing the amount of sustainable seafood provided and they are penalized for unsustainable practices or for under-harvest. Because fisheries and mariculture are separate industries with very different features, each is tracked separately as a unique sub-goal under Food Provision. The score for this goal is calculated through a volume-weighted average, where the the score of each sub-goal is multiplied by its proportion of the total food provisioning volume, and then combined in an average.

5.1.1 Wild-Caught Fisheries

This sub-goal describes the amount of wild-caught seafood harvested and its sustainability for human consumption. Higher scores reflect fishing practices with sustainably high yields that avoid excessive exploitation and do not target threatened existing fish populations.

This sub-goal measures the ability to obtain maximal wild harvests without damaging the ocean’s ability to continue providing similar quantities of fish for people in the future. The optimal levels are described by Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY). Higher scores reflect fishing practices with sustainably high yields that avoid excessively high exploitation, or over-fishing, and do not target threatened populations. Regions are penalized for resources that are either under-fished or over-fished because both of these conditions detract from the overall achievement of maximized food provision, although the penalty for under-fishing is lower than that for over-fishing, since it preserves the capacity to provide this benefit for the future.

Wild-caught fisheries harvests must remain below levels that would compromise the resource and its future harvest, but the amount of seafood harvested should be maximized within the bounds of sustainability. The reference point is set with a functional relationship. This calculation model aims to assess the amount of wild-caught seafood that can be sustainably harvested, with sustainability defined by multi-species yield, and with penalties assigned for both over- and under-harvesting. This is a departure from traditional conservation goals regarding wild-caught fisheries where under-harvesting is usually not penalized. In other circumstances, penalties are only given for over-harvesting, such as in the case for concerned fisheries managers who use over-harvesting as a way to guide enforcement. In the case of OHI, however, the idea is to assess the delivery of a sustainable benefit or the missed opportunity for one, and therefore any distance from the optimum is a penalty.

This sub-goal can interact with other goals and sub-goals through, for example through the destruction of surrounding habitats that can decrease the productivity of farmed fisheries indirectly or through by-catch which decreases the viability of biodiversity and iconic species.

5.1.2 Mariculture

Mariculture measures the ability to reach the highest levels of seafood gained from farm-raised facilities without damaging the ocean’s ability to provide fish sustainably now and in the future.

Mariculture practices must be sustainable and also maximize the amount of food production that is physically possible and desired by regional governments and those who buy, sell, and eat that food. This sub-goal shows whether or not maximal seafood yield from farm-raised facilities is occurring without damaging the ocean’s ability to continue providing seafood for people in the future. It is founded on the idea that mariculture practices must not inhibit future production of seafood in the area.

Higher scores mean that food provisioning is accomplished in a sustainable manner while not compromising water quality in the farmed area and not relying on wild populations to feed or replenish the cultivated species (i.e. the feeds are sustainable). A score of 100 means that a region is sustainably harvesting the greatest amount of farmed seafood possible based on its own maximum potential relative to the conditions of the assessment. Similar to the Wild-Caught Fisheries sub-goal, a low score can indicate one of two things: either species are either being farmed in an unsustainable manner, or assessed areas are not maximizing their seafood farming potential/target in their waters.

5.2 Artisanal Fishing Opportunities

The Artisanal Fishing Opportunities goal shows whether people with the desire to fish on small scales have the opportunity to do so.**

It is important to capture the degree to which a region permits or encourages artisanal fishing compared to the demand for such fishing opportunities, and if possible, the sustainability of artisanal fishing practices.

The artisanal fishing opportunities goal measures the opportunities for artisanal fishing rather than the amount of fish caught (covered in the Food Provision goal) or the household revenue earned from the activities (covered in the Livelihoods and Economies goal). In the Global Assessments, higher scores reflect high potential for the local population to access local ocean resources, regardless of whether or not those people actually do get access. This goal is about economic access, physical access, and access to the seafood itself. Economic access is comprised of needs and costs involved (such as fishing gear, fuel, vessel, etc.), and physical access is determined by how possible it is for individuals to get to the resource. Access to seafood is a reflection of how robust seafood populations are measured to be.

Damaging practices are sometimes used in artisanal fishing, such as the use of cyanide or dynamite, and these are penalized in the Index calculations. Such practices also lead Artisanal Fishing Opportunities to interact in a negative way with other goals.

5.3 Natural Products

The Natural Products goal describes how sustainably people harvest renewable non-food products from the sea. These include (but not limited to) shells, sponges, corals, seaweeds, fish oil, and ornamental fishes, fish for aquaria, sea salt, sea water, etc.

Natural Products evaluates the levels of sustainability for all non-food ocean-derived goods that are traded. It does not included products that are consumed for only nutrition, but may in some cases include products that are consumed as medicine. In the Global Assessments, the goal model calculates overall status by weighting the status of sustainable harvest of each extracted marine product by its proportional value relative to other harvested products. Higher scores reflect sustainable extraction of non-food ocean resources with little to no impact on surrounding habitats, marine species, or human well-being.

This goal does not include non-living items such as oil, gas, and mining products, because these practices are not considered to be sustainable (nor there could be a sustainable management target). They are also done at such relatively large scales that including them would essentially diminish the economic importance of other goods, resulting in an Index that focuses on the extraction of non-renewables. This goal also does not include any valuation of things like bioprospecting for medicines through genetic discoveries, which has an unpredictable potential value occurring in the future rather than current measurable values.

The activities that drive this goal can interact with other goals and sub-goals when unsustainable harvesting practices are used. Because so little is known about some of the functional relationships between the amount of natural products extracted and the effect of harvest on their quantities in the ecosystem, reference points are often based on educated assumptions applying the precautionary principle.

5.4 Carbon Storage

Carbon Storage describes how much carbon is stored in natural coastal ecosystems that absorb and sequester it in large amounts.

Carbon Storage evaluates the extent and condition of coastal marine habitats with high carbon storage capacity. In this case, “storage” means carbon sequestration. Highly productive coastal wetland ecosystems, like mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass beds, have substantially larger areal carbon burial rates than terrestrial forests. Coastal habitats therefore play a significant role in mitigating global carbon levels, and the health of these habitats is important because their destruction also releases large quantities of carbon into the atmosphere, damaging the overall health of coupled marine systems and exacerbating the impacts of global climate change.

In addition, these coastal habitats, so-called “Blue Carbon”, store carbon without causing acidification, and, contrary to open oceans, they provide a carbon storage service that can be affected by human actions such as conservation, and restoration efforts.

Because they store carbon for less than one hundred years, seaweeds and corals were not included in the Carbon Storage goal in the Global Assessments. While the pelagic oceanic carbon sink, consisting of phytoplankton, plays a large role in the sequestration of anthropogenic carbon, the pelagic ocean mechanisms are not amenable to local or regional management intervention. Phytoplankton contribute to carbon fixation when they die and sink to the sea bottom at sufficient depth, because it is effectively out of circulation. However, if those phytoplankton are eaten, the carbon is cycled back into the system and not sequestered.

Something that could potentially be included in the Carbon Storage goal in the future is mollusc shells, if they are added extracted and not recycled in the sea. So, if information on mariculture production and waste disposal are available, this could be an interesting addition to carbon storage at a regional scale.

5.5 Coastal Protection

Coastal Protection describes the condition and extent of habitats that protect the coasts against storm waves, erosion, and flooding. It measures the area they currently cover relative to the area they covered in the recent past.

Many habitats, including coral reefs, mangroves, seagrasses, salt marshes, sand dunes, and sea ice, act as natural buffers against storm damage and erosion. By protecting against incoming waves, flooding, and and other erosive factors, these living habitats keep people safe and help mitigate economic loss of personal and public property, cultural landmarks, and natural resources. The Coastal Protection goal assesses the amount of protection provided by marine and coastal habitats by measuring the area they cover now relative to the area they covered in the recent past.

Ideally, you would incorporate information for all habitats within regions of a study area, as well as information on the value of the land and the vulnerability of inhabitants being protected by these habitats. This would require data for each habitat type at a high spatial resolution as well as a measure of the value of what is protected by the habitats. The reference point for habitat-based goals will likely be a temporal baseline and historic data would be needed such that current habitat and value data can be compared to them.

The Global studies did not include an assessment of the protection provided by human-made structures such as jetties and seawalls, because these structures cannot be preserved without maintenance and do not constitute long-term sustainable services. They may also have other undesirable side effects, such as the altering of sedimentation rates causing erosion in new and unexpected locations. Although this phenomenon is closely tied to human habitation, it does not account for such things as property values as indicators but rather it focuses on what the habitats actually are and the protection that they provide.

5.6 Coastal Livelihoods and Economies

The Coastal Livelihoods and Economies goal rewards productive coastal economies that avoid the loss of ocean-dependent livelihoods while maximizing livelihood quality.

This goal is founded on two sub-goals: Livelihoods and Economies of ocean dependent sectors. Livelihoods measures of jobs and wages, and Economies measures revenues. The two halves of this goal are tracked separately because the number and quality of jobs and the amount of revenue produced are both of considerable interest to stakeholders and governments, and could show very different patterns, such as is the case when high revenue sectors do not necessarily provide large employment opportunities. The goal aims to maintain the number of coastal and ocean-dependent livelihoods (jobs) in a region, and maintain productive coastal economies (revenues), while also maximizing livelihood quality (represented by relative wages).

Maintaining jobs in this case means not losing jobs (or that it keeps pace with national employment trends in other sectors) – this sub-goal does not give credit for gaining jobs in the Global Assessments. It does not attempt to capture aspects of job identity like reputation, desirability, or other social or cultural perspectives associated with different jobs, nor does it account for the impact upon an individual but rather focuses on the aggregate. One can examine the component parts that make up this goal, however, to evaluate individual sectors and infer implications for job identity.

5.6.1 Livelihoods

The Livelihoods sub-goal describes livelihood quantity and quality.

This sub-goal evaluates the quantitative and qualitative benefits workers get from the oceans in the form of jobs and wages. In the Global Assessments, the two sub-components are equally important because the number of jobs is a proxy for livelihood quantity, and the per capita average annual wages is a proxy for job quality. Some relevant sectors include tourism, commercial fishing, marine mammal watching, and working at ports and harbors, among others. Jobs and wages produced from marine-related industries are clearly of huge value to many people, and directly benefit those who are employed–they also benefit those who do not directly participate in the industries but rather gain indirectly (known in economics as multipliers) from the value of community identity, tax revenues, and other indirect economic and social impacts of a stable coastal economy.

5.6.2 Economies

The Economies sub-goal captures the economic value associated with marine sectors deriving ocean-dependent revenue.

The Economies sub-goal evaluates the revenue generated from marine-based industries. Strong coastal economies are something that people value, and this can be reflected by the GDP generated by these coastal regions both directly and indirectly. The economies sub-goal is composed of a single component, revenue.

The definition of a marine-related sector can vary. There are jobs that are directly connected to the marine environment, such as shipping, fishing, longshore workers, but also some that are connected indirectly, such as supplies and supporting industries. The use of multipliers in attempts to capture the indirect revenue generated by jobs more indirectly associated to marine sectors is a well-established method in economics, and is encouraged in this approach.

5.7 Tourism and Recreation

The Tourism and Recreation goal captures the value people have for experiencing and taking pleasure in marine and coastal areas.

Tourism, travel, and recreation are major drivers of thriving coastal communities and they also offer a measure of how much people value ocean systems. By electing to visit a coastal area rather than an inland area, people express their preference for visiting these places over others. Ideally, tourism and recreation could continue indefinitely if it is done in a sustainable manner.

Ideally you could directly measure the tourism and recreation activities people engage in such as visiting beaches and marine parks, surfing, SCUBA diving, snorkeling, marine mammal watching, canoeing, kayaking, boating, fishing, sailing, swimming, etc. In most cases, however, such information is not available, so you can use proxy data to estimate the value in experiencing tourism and recreation. For example, employment in coastal tourism could be used as an indirect measure of tourism health, assuming that robust proportional employment in tourism is strongly correlated with a strong tourism sector. Therefore, you could use data for employment in coastal tourism industries, which could include accommodation services, food and beverage services, retail trade, transportation services, and cultural, sports and recreational services, and could exclude investment industries and suppliers.

This goal does not include the revenue or livelihoods that are generated by tourism and recreation; that is captured in the Livelihoods and Economies goal. This goal is not about the economic benefits, but instead about the value that people have for experiencing and enjoying coastal areas.

5.8 Sense of Place

The Sense of Place goal aims to capture the aspects of coastal and marine systems that people value as part of their cultural identity and connectedness to the marine environment.

The Sense of Place definition includes people living near the ocean and those who live far from it and still derive a sense of identity or value from knowing particular places or species exist. Since few groups, communities, or states have explicitly described the attributes of the coastal and ocean environments that have special cultural meaning to them, the Index assesses how well this goal is being delivered through the conditions of two sub-goals, Iconic Species and Lasting Special Places. The overall goal score is then the arithmetic mean (average) of the two sub-goal scores.

5.8.1 Iconic Species

The Iconic Species sub-goal assesses the threat to species that are culturally and/or socially important to a region.

Iconic Species are defined as those that are relevant to local cultural identity. The intent of the sub-goal is to focus on those species widely perceived as iconic within a region, and iconic from a cultural or existence value. This is in contrast to an economic or extractive reason for valuing the species. Iconic species symbolize the cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic benefits that people hold for a region, often bringing intangible benefits to coastal communities and beyond.

They can be identified through activities such as fishing, hunting, commerce; through local ethnic or religious practices; through existence value; and through locally-recognized aesthetic value. This can even include, for example, touristic attractions and iconic species as defined by their repeated representation in local art.

This type of assessment stands in contrast to economic or extractive reasons for valuing the species. Because almost any species can be iconic to different groups or individuals, defining which species are culturally iconic can be challenging. Thus, it is important to establish objective criteria for determining what is considered an iconic species in the study area. Information can sometimes be found from local customs and experts, oral tradition, sociological or anthropological literature, journalism, and regional studies.

5.8.2 Lasting Special Places

The Lasting Special Places sub-goal captures the conservation status of geographic locations that hold significant aesthetic, spiritual, cultural, recreational, or existence value for people.

The Lasting Special Places sub-goal focuses on those geographic locations that hold particular value for aesthetic, spiritual, cultural, recreational or existence reasons. It is different from quantifying protected areas because it attempts to contain the value of sustainability for human interaction. Well-maintained and protected lasting special places provide intangible but significant resources that help sustain and may also generate economic opportunities and help to sustain coastal communities, but those are captured in other goals.

This goal is hard to define in terms of data. Other goals capture the economic benefits derived from Lasting Special Places, as well as biodiversity. This goal assesses the human-use and assumes sustainability through aesthetic, cultural, and other kinds of engagement.

5.9 Clean Waters

The Clean Waters goal captures the degree to which local waters are free of natural and human-made pollutions.

Clean Waters are important to both people and the marine life on which they depend. People enjoy having unpolluted estuarine, coastal, and marine waters both for their aesthetic value and for their importance to health. Sewage pollution, nutrient runoff, chemical pollution, and marine trash all make coastal waters less clean. This leads to human problems, such as fecal coliform ingestion, and ecosystem problems like eutrophication and algal blooms.

Ideally, you would include information on many different categories of marine pollution to best capture the factors that can cause waters to become unsuitable for recreation, biodiversity, human health, or other purposes. Contaminants often include contaminants, including organic pollutants, inorganic pollutants, metals, oils, turbidity, and trash.

5.10 Biodiversity

The Biodiversity goal captures the conservation status of marine species.**

Biodiversity measures the condition of species and key habitats that support species richness and diversity. It is is measured through two sub-goals: Species and Habitats. Species were assessed because they are what one typically thinks of in relation to biodiversity, and people value biodiversity in particular for its existence value. But because only a small proportion of marine species worldwide have been mapped and scientifically assessed, habitats are used as a proxy for the condition of the broad number of species that depend on them. A simple average of these two sub-goal scores produces the Biodiversity goal score in the Global Assessment.

5.10.1 Species

The Species sub-goal aims to estimate how successfully the richness and variety of marine life is being maintained.**

The Species sub-goal aims to estimate how successfully the richness and variety of marine life is being maintained. People value the species that comprise marine biodiversity for their existence value as well as their contributions to resilient ecosystem structure and function. The risk of species extinction generates great emotional and moral concern for many as well.

Ideally, you would use available on the number of species in each region of a study area, along with their habitat ranges, and assessments of their population size or conservation status. Assessment of the conservation status should be undertaken by a trusted authority, such as the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). China, for example, has its own equivalent to the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. If a country has conducted its own species surveys and assigned categories of risk, that information may be more useful than the global data not specialized to the local context.

The Species sub-goal is conceptually equal to iconic species, but it includes all species that are scientifically assessed, not just those that are culturally important. This will limit your data to those species that have this kind of information. The species data layers in the Global Assessments included the amount of area where each species is present, so that species that inhabit a greater area have a greater weight in the calculations than those with a smaller range. This was different from the Iconic Species approach.

5.10.2 Habitats

The Habitats sub-goal measures the extent and condition of habitats that are important for supporting a wide array of species diversity.

Habitats are areas where animals can thrive and bring further positive benefits–whether for existence value or for other enjoyment. The amount of area needed to ensure biodiversity varies with habitat type and animal size, so therefore this is an indirect approach to representing the status of biodiversity.