Overview

11 years of OHI Scores!

Tue, Dec 06, 2022

We are proud to announce our 11th (!) year of measuring the state of the world’s oceans.

The global Ocean Health Index (OHI, for short) measures how well we are managing the sustainable delivery of 10 benefits, or goals, that people want and need from the ocean.

As usual, the 2022 assessment includes a new year of data, calculated using the most recent data available from agencies and other sources. Given our commitment to using the best available science, we also updated previous years’ scores (2012-2022) using the latest science and data when available. As always, the data and code underlying these results are publicly available (Data preparation and Score calculation).

This year’s assessment was led by the OHI fellows Juliet Cohen, Peter Menzies, and Cullen Molitor, and NCEAS scientists Gage Clawson, Melanie Frazier, and Ben Halpern.

Overview of Results

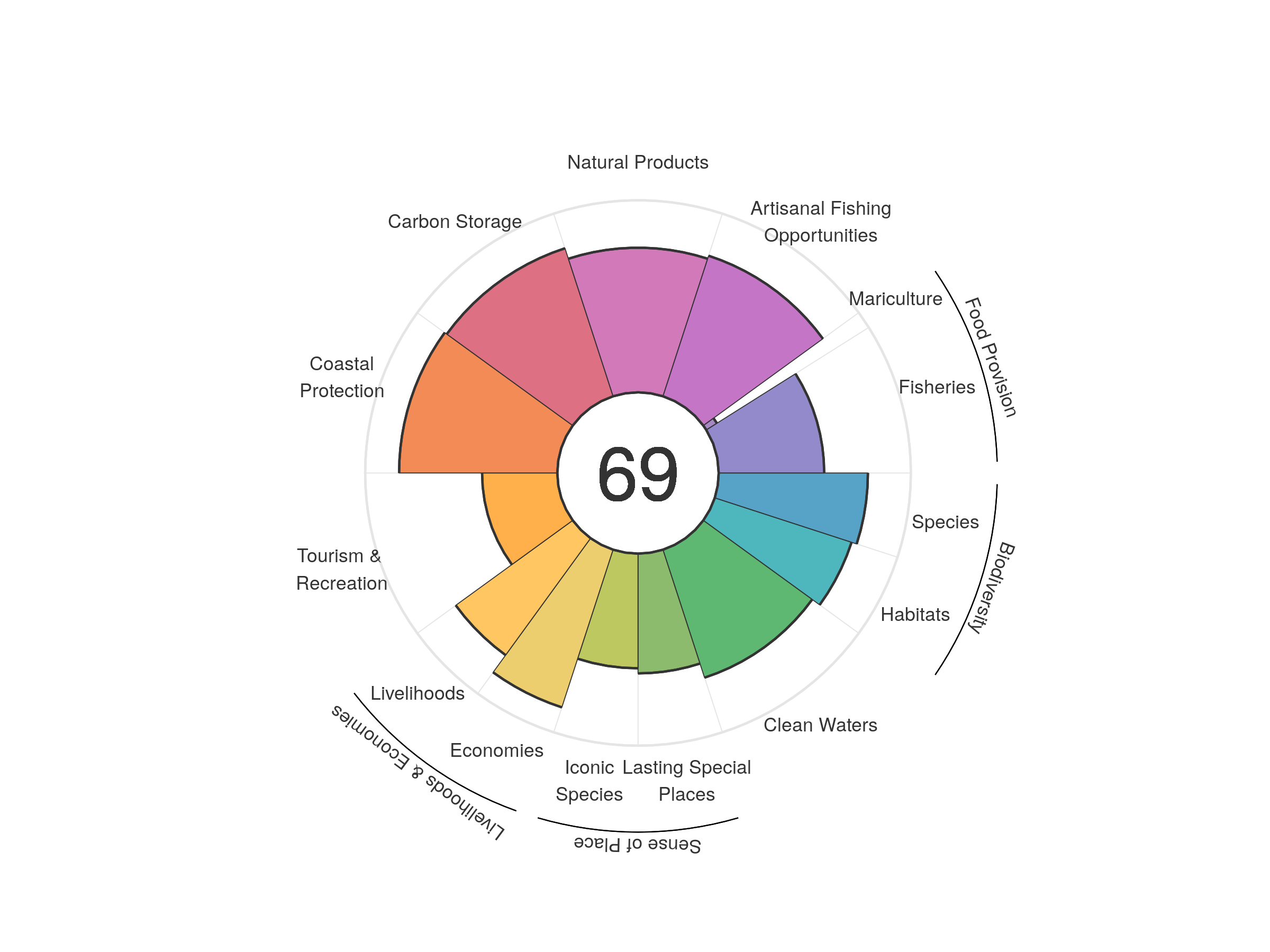

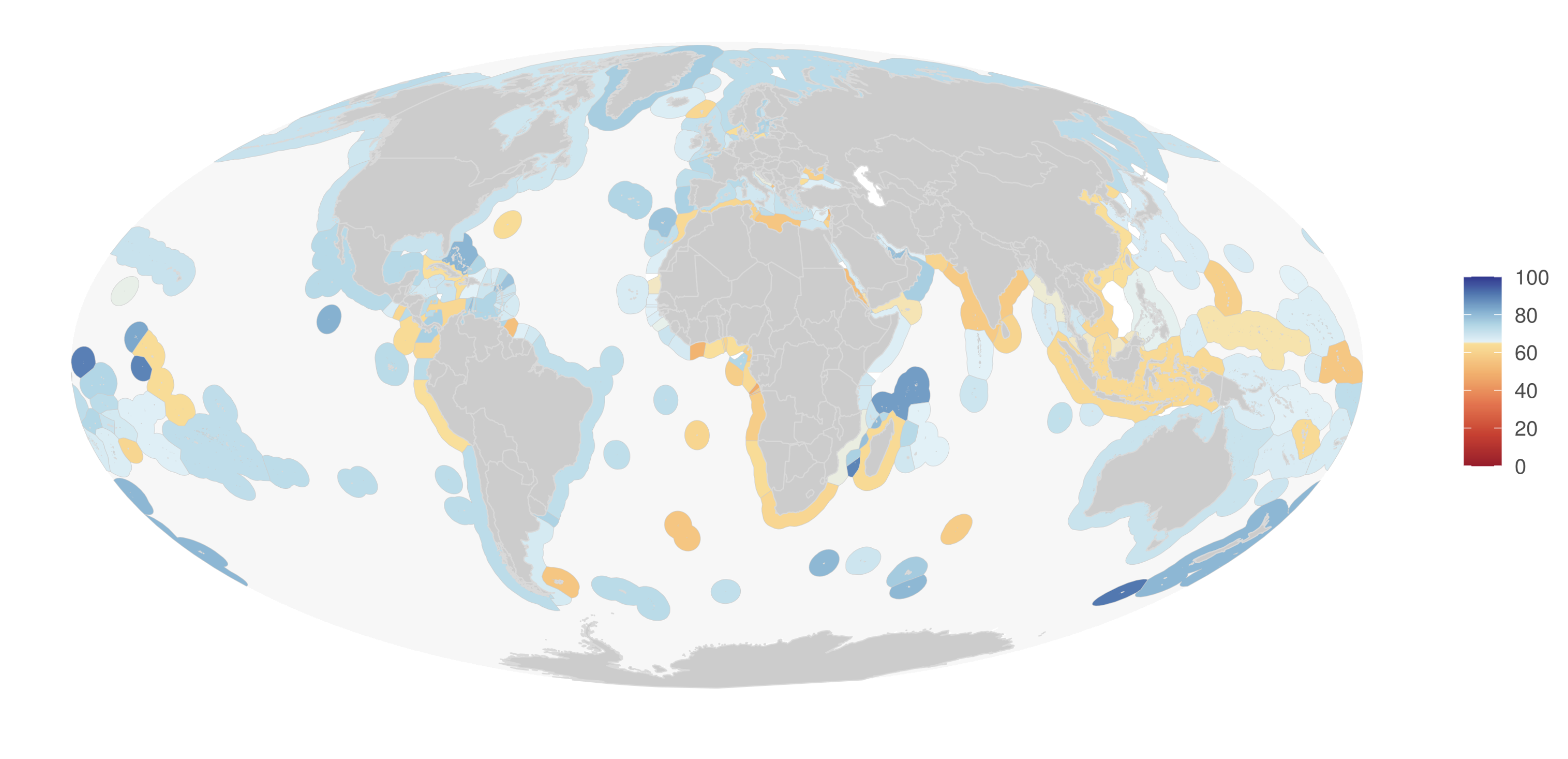

The overall global index score was 69 (Figure 1), which is similar to previous years. The regions with the highest scores tend to be uninhabited, or low human population, islands, although New Zealand, Bahamas, and the United Arab Emirates also have relatively high scores (Figure 2). Regions with lower scores tend to be in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Asia.

Figure 1. Flower plot describing the average 2022 global Ocean Health scores (eez area weighted average of region scores) for the overall Index (center value) and goals/subgoals (petals).

Figure 2. 2022 Ocean Health Index scores for 220 regions.

Although overall index scores have hovered around 70 since 2012, a deeper dive into the index reveals some interesting trends and patterns.

Scores for many regions are reasonably good, and global scores have increased since 2012 for some goals, such as: sense of place and clean waters. However, we observed some worrisome patterns for fisheries, iconic species, species condition, and tourism & recreation (due to the economic downturn of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Table 1. Ocean Health Index, global scores (eez area weighted average of region scores) for the Index and goals/subgoals for all years.

| goal | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Index | 71.5 | 72.2 | 72.9 | 73.4 | 73.5 | 73.5 | 73.7 | 73.8 | 73.9 | 73.7 | 73.9 | 69 | 68.8 |

| 2 | Artisanal opportunities | 75 | 75.5 | 75.5 | 75.4 | 74.9 | 74.5 | 74.5 | 74.2 | 74.9 | 74.5 | 76.4 | 76.8 | 76.9 |

| 3 | Species condition (subgoal) | 79.9 | 79.9 | 79.7 | 79.4 | 79.2 | 78.9 | 78.7 | 78.5 | 78.2 | 78 | 77.7 | 77.5 | 77.2 |

| 4 | Biodiversity | 78.6 | 78.1 | 78.3 | 78.4 | 77.9 | 77.4 | 77.2 | 76.8 | 76.4 | 76.4 | 76.3 | 76.3 | 76.1 |

| 5 | Habitat (subgoal) | 77.4 | 76.3 | 76.8 | 77.4 | 76.6 | 75.9 | 75.8 | 75.2 | 74.7 | 74.8 | 74.9 | 75 | 74.9 |

| 6 | Coastal protection | 80.1 | 80.1 | 82.6 | 82.6 | 82.4 | 82.1 | 82 | 81.7 | 81.7 | 81.9 | 82.3 | 82.8 | 83 |

| 7 | Carbon storage | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 81.1 | 81.1 | 81.1 | 81.1 | 81.1 | 81.1 | 81.1 |

| 8 | Clean water | 69.2 | 69 | 69.5 | 69.6 | 69.6 | 69.9 | 70.2 | 70.8 | 71 | 71.2 | 71.1 | 71.3 | 71.3 |

| 9 | Fisheries (subgoal) | 54.5 | 54.9 | 54.8 | 54.6 | 54.2 | 54 | 53.5 | 53.9 | 54.1 | 54.5 | 55.1 | 55 | 54.9 |

| 10 | Food provision | 50.7 | 51.1 | 51.1 | 50.7 | 50.4 | 50.1 | 49.5 | 49.7 | 49.6 | 49.7 | 50.1 | 50.1 | 50.1 |

| 11 | Mariculture (subgoal) | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 6.9 |

| 12 | Iconic species (subgoal) | 66 | 66 | 66.8 | 66.9 | 67.6 | 67 | 67 | 67.7 | 65.3 | 63.3 | 62.9 | 62.8 | 62.8 |

| 13 | Sense of place | 60.4 | 61.1 | 61.4 | 61.9 | 62.4 | 62.6 | 63.5 | 64.4 | 63.6 | 62.8 | 62.6 | 62.4 | 62.4 |

| 14 | Lasting special places (subgoal) | 54.9 | 56.1 | 55.9 | 56.9 | 57.1 | 58.3 | 60.1 | 61.1 | 61.9 | 62.4 | 62.2 | 62 | 62 |

| 15 | Natural products | 75.2 | 75.7 | 76.5 | 76.7 | 76.6 | 76.3 | 75.8 | 74.1 | 74.3 | 72.8 | 73.4 | 73.7 | 74.3 |

| 16 | Tourism & recreation | 69 | 72.4 | 75.1 | 80.9 | 84.2 | 86.7 | 88.6 | 91.5 | 92.1 | 92.8 | 92.3 | 22.4 | 18.4 |

MORE RESULTS

Below we take a deeper dive into some of the interesting patterns we observed in the data for specific goals and regions.

Food provisioning

One of the most fundamental services the ocean provides is the provision of food. Fish provide nearly 20% of global animal protein, helping to meet the basic nutritional needs of over half of the world’s population (FAO 2020)!

Given the importance of marine fisheries as a source of food, the apparent decline in scores is potentially alarming. Over the past 10 years, there has been a slight decrease (~1%) in fish catch (2009/2010 vs. 2018/2019). However, the differences in catch are drastically different across regions, ranging from 200% more to 1% less, which can produce many different outcomes for fish stocks depending on the status of the stock (underfished, fully exploited, overfished). 119 of the 220 regions included in OHI have a fisheries score less than 50. Small island nations tend to have high scores, and Nauru is the highest scoring region for the fisheries subgoal in 2022.

Marine aquaculture also provides large quantities of food; however, this is an underutilized resource with only a handful of countries reaching their potential. Countries that appear to be reaching (likely the low end of) their sustainable potential include: Germany, Finland, Denmark, South Korea, Netherlands, and Spain. And several countries have had marked increases in recent production, including: Germany, Ecuador, Malta and Turkey. This goal will be interesting to watch in coming years as mariculture production continues to increase, and the sustainability of mariculture practices become better understood.

Sense of place

People derive a sense of identity or value from living near the ocean, visiting coastal or marine locations or just knowing that such places and their characteristic species exist.

One way we attempt to capture this goal is through the lasting special places subgoal which measures how well we are protecting marine resources by establishing Marine Protected Areas, MPAs. A perfect score indicates a region is protecting 30% of the inland area and 30% of the marine offshore area. This reference point was established given the Global Ocean Alliance’s call to protect 30% of the ocean by 2030 (e.g., https://www.oceanunite.org/30-x-30/)

Exciting news: The global score for the lasting special places subgoal has steadily improved from 2012 to 2022 because many countries have established coastal and marine protected areas. In fact, one of the most common ways countries have improved their Index scores is through the establishment of protected areas. Currently, 72 of the 220 coastal countries and territories protect at least 30% of their coastal areas. This has been a substantial improvement since 2012, when we started the Index, when 51 coastal countries and territories had met this goal. This demonstrates the remarkable effectiveness of programs encouraging conservation.

Clean waters

Clean water in marine environments is valued for aesthetic, health, and environmental reasons. The clean waters goal measures contamination due to chemicals, excess nutrients, trash, and pathogens.

Overall, the Clean Waters goal has increased modestly since 2012. The global score has, on average, increased by one fifth of a point every year since 2012. This increase is likely due to a decrease in human derived pathogens in waterways (more people have access to improved sanitation facilities), and a decrease in land-based nitrogen input associated with manure and fertilizer application.

For synthetic fertilizers, the past 11 years have witnessed about a 12% increase in fertilizer use (2010/2011 vs. 2010/2020), however, the trend varies dramatically by country. Some of the countries with the largest coastlines and most fertilizer use have actually witnessed a decrease in fertilizer use. For example, mainland China which uses nearly 30% of global fertilizer has decreased their fertilizer use by 11% in the past 11 years. The United States has decreased their fertilizer use by 2.3% over the same period, which actually results in a fairly substantial decrease in global fertilizer use because they account for about 11% of global fertilizer consumption. Germany has decreased their fertilizer use by an impressive 23% during the same period. Of the 166 countries reported by FAO, 49 of them have had a decreasing trend in fertilizer use from 2010-2020.

Media

Taking Ocean Vital Signs in the UCSB current.